The Fertility Crisis; More Than You Wanted To Know

Making Common Arguments & Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

Many people seem to be obsessed with fertility, i.e. they want people to have more kids. Why is this? The world is not dangerously underpopulated. -

I recently saw the above quote on my substack feed, and I realized that the Fertility Crisis being a major problem isn’t immediately obvious to many, or even most people. I’ll try in this article to communicate a history of worrying about demographics, make clear what exactly “The Fertility Crisis” is, why I believe it’s a problem, and maybe some possible solutions.

I. Background Information

1. Carrying Capacity

Before understanding what the Fertility Crisis is, it’s absolutely necessary to know about the other demographic problem that preceded it. The ancient Greek writer Xenophon observed how rabbits tend to increase their population to the maximum level that their environment can support. Since then, this understanding has expanded and is now applied broadly across species, highlighting how all organisms tend to grow to the limits of their habitat's resources. National geographic defines the carrying capacity as “a species' average population size in a particular habitat. The species population size is limited by environmental factors like adequate food, shelter, water, and mates. If these needs are not met, the population will decrease until the resource rebounds.”

As you can see in the above graph, after a period of exponential growth, eventually a species reaches carrying capacity, then experiences oscillations of growth and decline centering on that capacity. This isn’t a comfortable equilibrium, as it entails continuous overshooting and subsequent starvation for much of the population, and much harder competition for those lucky survivors. This is as close to a scientific principle you can get, as basically any species upon being introduced to a new environment will follow this growth curve, from the top predators like killer whales and wolves down to the smallest bacteria.

2. Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus, in his famous essay An Essay on the Principle of Population, took this principle to its logical conclusion applied to humans in the European world of 1798 . As he saw it, we had been successfully staving off the carrying capacity of the European continent for centuries through increased efficiency and improved agricultural technologies, but this only had the effect of pushing the carrying capacity of the environment for humans higher. A delay, not a solution. While in the exponential growth stage there was no reason to expect famine, but the party had to end when we outgrew our food production. Malthus feared this would lead to mass starvation and unprecedented human suffering. The ominous name for the predicted population collapse post-exceeding-carrying-capacity was a Malthusian Collapse.

The proposed solution to this (obviously named Neo-Malthusianism) was human population planning (remember this for later) which proposed both passive incentives and active authoritarian structures to reduce the number of children people were willing, or were allowed to have. This was justified in the face of the impending doom with immeasurable imminent future suffering.

Now, the original theory was sound, but its assumptions were wrong. Malthus assumed that population growth would only accelerate, as there was no reason in his time to assume much would cool the natural desire to reproduce. Contrary to his beliefs, population growth naturally slowed in Europe faster than expected due to hard to specify factors like;

Outbound emigration to colonies

Urbanization (Leading to lower fertility)

Secularization (Leading to lower fertility)

Improved Education (Leading to lower fertility)

Improved Agricultural Production (Leading to a higher carrying capacity)

These (and others I may be forgetting) factors worked against a malthusian collapse. I’ll call them anti-malthusian factors for simplicities sake.

There were also factors working for a malthusian collapse that Malthus had not originally predicted. Chiefly among them was the rapid reduction in infant mortality resulting from improved medical care in the 19th century (although increasing life expectancy was also at play here). This had a strong upward pressure on population growth, as even if people were having less children, more of those children lived beyond the age of 4.

The effect of all this was that a malthusian collapse never occurred in Europe, but the logic of the argument was sound, and has been empirically confirmed time and time again in other species. If population growth ever exceeded carrying capacity, and carrying capacity didn’t increase along with population growth, we have every reason to expect Malthus would have been right.

Malthusian ideas were prominent at least until the 1970s, with The Population Bomb being the bible of demographic problems for the Cold War west. The theory went, (exactly as Malthus once predicted), a new population crisis was preparing to explode. Their focus wasn’t so much of the west, but on the rapidly growing regions of Asia and Africa, who had yet to experience much of a reduction in fertility, but were largely benefiting from important infant mortality reduction techniques (things as simple as “Wash Your Hands”). This was the state of demographic concern until for most of recent history, but things started to change around the 1970s.

3. Modern Neo-Malthusianism

As we’ve seen, thanks to a variety of factors Europe went through a gradual decline in population growth, a gradual increase in carrying capacity, and a cursory look at European history will reveal very few major famines barring wars or government engineering. Carrying capacity was clearly never reached, and Europe prospered.

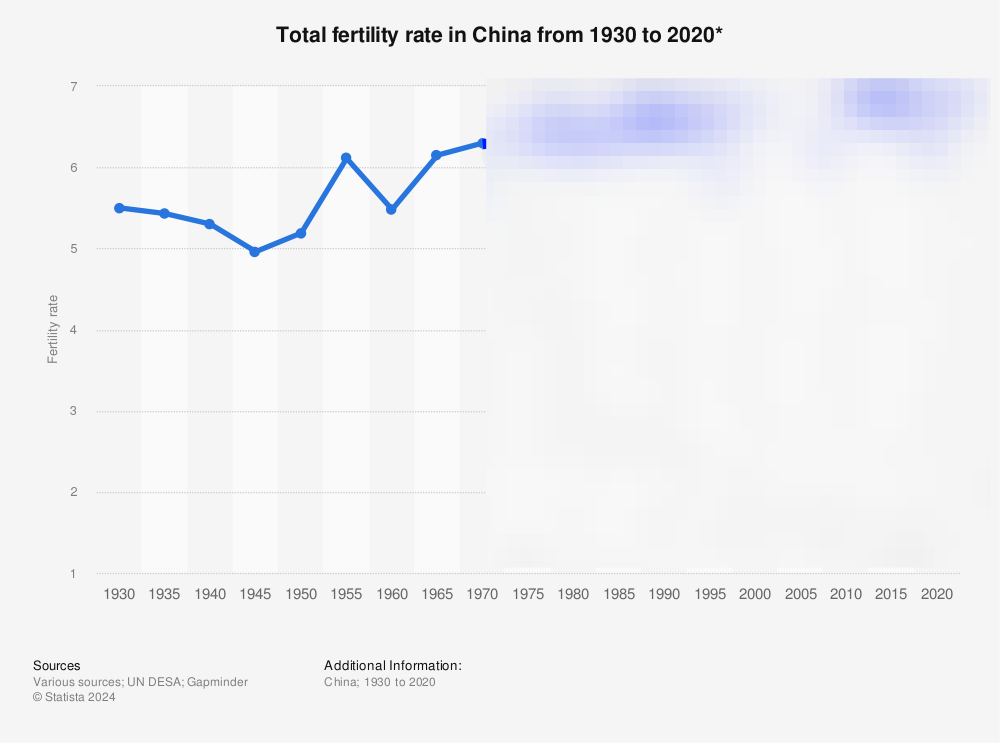

Now what of the rest of the world? Europe was fortunate enough that it was able to balance an increasing carrying capacity with a gradually decreasing infant mortality so that they avoided collapse. Other countries which sought shock therapy modernization were in a much more precarious position. China was the focus of The Population Bomb for it’s 6.3 births per woman when the book was written, and it will be our chief example of how population planning and rapid modernization worked together to successfully prevent a malthusian collapse.

6 births per woman is a lot. Seriously. At that rate, every new generation would be approximately 3x larger than the previous. After a century compounding at this rate would have the population 81x larger than 100 years before. Considering China’s population was already over 800 Million in 1970, you can see the concern.

By 2070 there would be approximately 65 Billion people living in China.

No matter how much of a techno-optimist you are, no amount of vertical farming and land reclamation could make feeding that many people possible within the next half century.

So the world was doomed. The third world was growing too fast, and with their numerically superior armies they might just march over the rest of the world in search of new farmland like the Proto-Indo-Europeans of the past. Wait a second… I just looked out my window and there aren’t a billion Chinese people living in New York. Apparently something happened in 1970 that caused fertility to drop more than expected, and basically invalidated every prediction of the Population Bomb. The world is saved from a Malthusian collapse. Yay!

So what exactly happened? Well, a serious analysis of what went on in Maoist China to reduce fertility could fill an entire book. Suffice it to say that it was a combination of the anti-malthusian factors I mentioned earlier and a bit of government intervention. It would be easy to blame the famous 1-Child policy for this, but that was implemented in 1980, a decade after the monumental decline in fertility.

II. Beyond Malthus.

We’ve made it. Thanks to the wonders of modern western science and culture we’ve globally reduced fertility to the point there is very little worry of a global malthusian catastrophe. There’s some bits of overpopulation here and there, but even absent serious government intervention, it seems that this whole malthusian problem was a problem for the animals, and humanities natural behavior has immunized us.

I honestly can’t understate how great of a thing it is that we avoided overpopulation to a dangerous extent. There’s few worse forms of suffering than starvation, and I’m incredibly grateful population growth has slowed worldwide.

The forces that worked to prevent a population explosion didn’t go away though. Upon hitting replacement level fertility, we didn’t decide to stop secularizing, decrease education spending or reverse urbanization, mostly because the causes of these trends had nothing to do with fear of Malthus in the first place. We secularized thanks to rationalist thinkers, increased our level of education for the prosperity a well educated person can achieve, and urbanized because people like being in cities, where there’s a lot to do, and ample opportunities. Once we had reached the goal of replacement level fertility, and the malthusian concerns past their expiration date, the fertility rate continued to drop.

1. <2.1 Fertility Rate

The replacement rate, the number of births at which population will remain stable, is 2.1 births per woman. Above this number, and the population will grow. Below this number, and the population will shrink. If the fertility rate is 1, every generation will be half as large as the last, and if the fertility rate is 4, every generation will be twice as large as the last.

Outside of a few minority western cultural subgroups like the Amish, Haredim or the Mormons, every single western country has below replacement level fertility (with one exception). But why is this a concern? As the original quote that prompted this essay said, why should we obsess over fertility? It’s not like the world is dangerously overpopulated.

2. Fertility decline is largely synonymous with cultural decline.

Cultures are perpetuated by the people within them. Usually, although not always, a culture preserves itself through raising children within that culture, ensuring there’s a consistent or growing population to preserve the values, language and cultural norms throughout the centuries. A major reason the unique Spartan culture in ancient Greece died off was their criteria for being a citizen was so strict, the number of children who qualified was always becoming smaller and smaller.

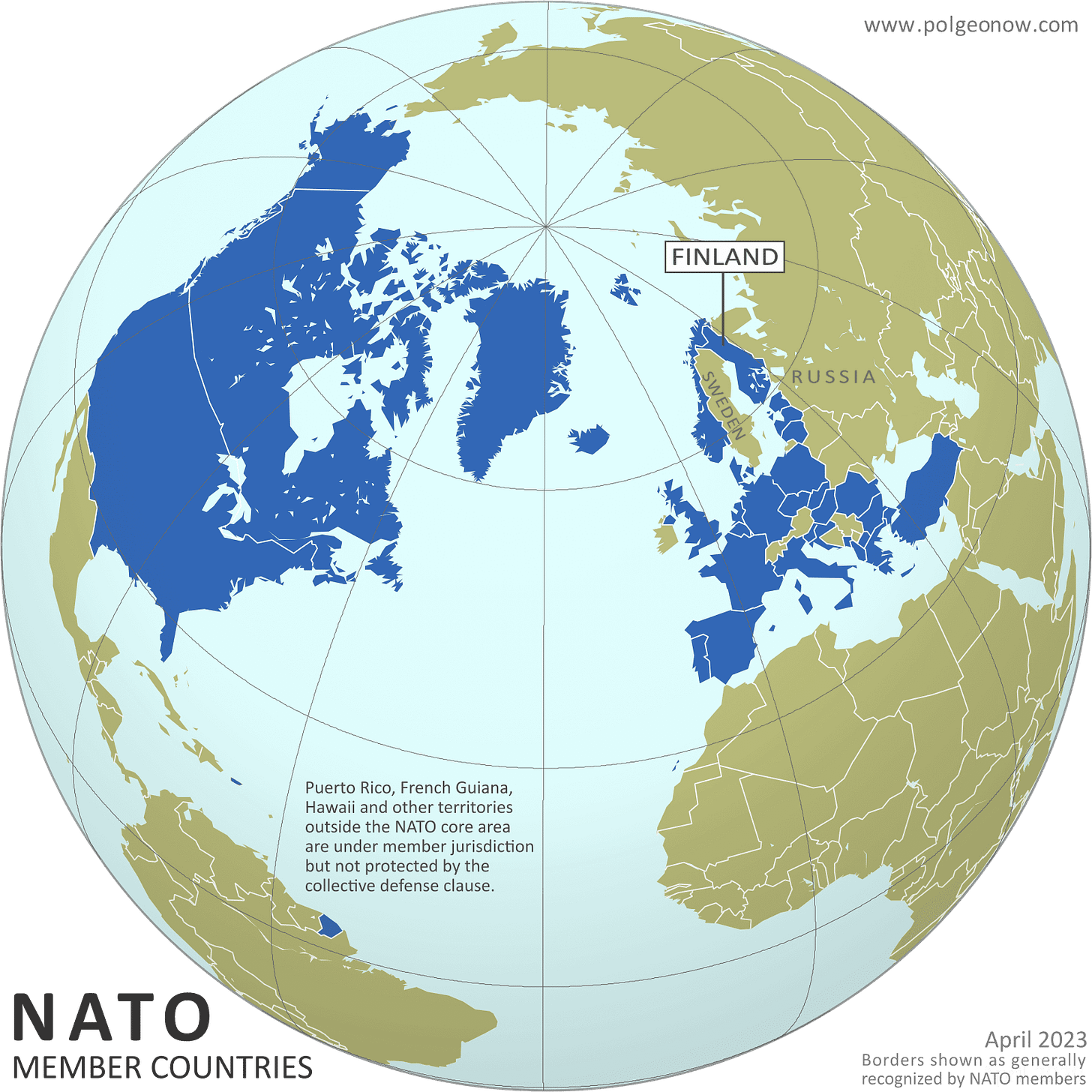

Sometimes, when a culture stops perpetuating itself, it is superseded by another. Either through population replacement, or cultural conversion, there are ample examples of more competitive cultures overtaking less competitive ones. Around 5,000 BC, Europe was completely populated by peoples who spoke indigenous languages to the continent, the vast majority of which are completely unknown. Over the next few thousand years, the languages, and certainly many of the cultural practices that went along with those languages were replaced by Indo-European speaking peoples. While there was certainly significant intermixing, the only three groups in Europe who speak a language preserved from before this time are the Finish, Estonians and Basque.

A more historical, rather than archaeological or linguistic example was the Roman conquest of Gaul, in modern day France. Originally populated by Celts, Julius Caesar conquered the province in the name of Rome shortly before his famous politicking in Rome.

Out of 3 million Gauls, one third was killed and another third was enslaved.

- Gaius Julius Caesar

Caesar was famous for his campaigns in Gaul, where in just a few years he claimed to have killed a third of the population, enslaved another third, and for remaining third.. he just hadn’t gotten to yet. A few hundred years later, the population of Gaul was speaking Latin, they were living in Roman style villas and towns, with a society organized around Roman values. It is no exaggeration to say that the Gallic culture had been completely replaced and superseded by the Roman culture.

Now what does this have to do with fertility? If your neighboring culture is busy having 5 kids, and you’re busy having 1, in a few generations your neighbors culture will be 50 times larger. It’s not hard to predict where this trend takes you over the next century or two.

If you believe that your culture is worth preserving this is a serious concern.

3. Fertility decline leads to decreased international power.

There’s a reason China has a lot more global influence than Luxembourg, and it’s not because they have less than a fifth their GDP per capita. It’s indisputable that population loosely equates with international influence, and some powers are clearly better international hegemons than others.

While many might complain about the US dominated international system, and justly so, I don’t think anyone in the west could seriously consider China, Russia, or any Middle Eastern Country a better alternative. Maybe there would be no new global hegemony to replace the West, but there would certainly be spheres of influence. I think the neighbors of every authoritarian bully out there (See: Ukraine) understand that the rules-based post WW2 system is far superior to one where might-makes-right.

If you’re from a country that you believe is a better international mediator than an authoritarian China, then your country’s worsening demographics are a concern.

4. Dependent Old People Are Expensive

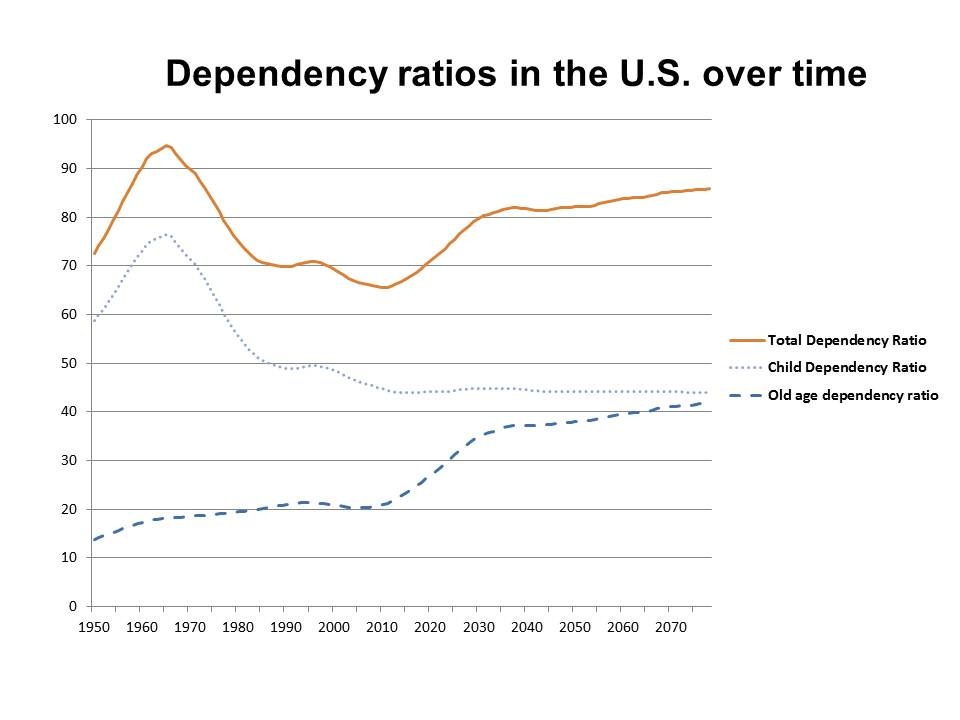

The more retired vs. young people you have in a society, the more resources working age people have to expend to keep them alive and comfortable. The ratio of elderly to working age people can largely be captured in the old age dependency ratio.

While we’ve had higher overall dependence ratios in the past thanks to high numbers of children. Children can be considered investment into the future. A couple of decades spent on childcare and education creates a productive worker with ~4 decades of productivity they repay to society. A couple of decades of elder care ends with a dead body.

The ratio can be largely interpreted as “How many dependents are there for every working age adult?” On this chart, 10% equates to about 10 adults for every elderly dependent, while 50% would equate to 2 adults for every elderly dependent.

Social security and pension systems weren’t designed for so many people retiring all at once without the replacement of new young workers. Fundamentally, there is not enough money saved up to pay for the elderly, so we’ll need to find a solution.

France has recently dealt with this problem (temporarily) through pension reform. They knew they were going to run out of money in their pension system so they had to pick from one of 3 options;

Higher Taxes

Lower Pension Payments

Raise Retirement Age

France went with option 3, raising the retirement age 2 years from 62 to 64. This pushed back the problem a few years, but by no means solved it. Remember how much they protested this? Imagine what will happen when more serious reform becomes necessary. This is only the beginning.

III. So What Do We Do?

By now you might acknowledge that population decline is a problem, and hopefully you’ve been able to shake the pervasive shadow of Malthus, now forgetting about overpopulation. If you acknowledge the problem for what it is, the next obvious step are looking for solutions. Obviously the simplest solution is to just have more children. If a country’s fertility rate is stable, or even only slightly negative (negative meaning less than 2.1), then the elderly dependency ratio won’t be too burdensome, cultural decline wouldn’t be so pronounced, and relative weakening of national power would be less of a concern. So what sort of policies do we have to boost fertility?

1. Hungary.

Victor Orban’s right-leaning government in Hungary has made low fertility a primary political issue. Born from worry about Hungary’s language, culture and people being replaced by foreign influence and immigrants, Hungary has developed a seeming obsession about fertility. Hungary spends about 5% of their GDP on policies meant to encourage fertility, which is more than the US spends on military expenditures, so you know Hungary is serious. So what are the results?

Orban came to power around 2000, and only started pushing fertility strongly around 2010, so apparently his policies have had some effects. Fertility has gone from around ~1.3 to ~1.6, which is a definite improvement. This is very encouraging, but let’s not speak too soon.

One of Hungary’s neighbors, Czechia has spent far less than Hungary on fertility, and they have seen an even larger jump in fertility. From a low of ~1.2, they’ve reached as high of almost 2. That’s nearly replacement level fertility! Whatever the Hungarians have been doing, it hasn’t been working nearly as well as the Czech ambivalence to the problem.

Unfortunately, what we’re seeing in both these graphs is likely not a long term rebound in fertility. Most post-soviet countries have experienced this rebound from their 1990’s lows, followed by an unfortunate trend of decline. This has happened in Russia, Ukraine, Lithuania, Poland, what was once East Germany, and more. It seems that the post-soviet economic malaise was a temporary blow to fertility, and as that was alleviated we were rewarded with a rebound, before the more general trend of decline kicked back in. At this point it’s unclear if Hungary’s policies have even done anything.

Another blow to morale is how this decline is likely to impact future generations. The echoes of WW2 can still be seen every 25 years in Russian and Belarusian demographics due to the large cohort of missing young men. The poor demographics of the 1990s is due for an echo 25 years, which happens to be right about now.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s reason to be optimistic, but the increase in fertility can certainly not be attributed to any intent to fix the problem.

2. South Korea

If you thought Europe was bad, wait until you see the Asian Tigers. South Korea, worst of them all, currently has a fertility rate of 0.7. This is abysmal. At this rate, every subsequent generation will be a third the size of the previous one.

By the end of the century South Korea might have a generation as small as 5% what the current one is. With the same trend, there would be 0.1% as many south Koreans being born as there are right now by 2175. It’s a complete crapshoot to try and predict anything 150 years into the future, but this just serves to illustrate the potentially disastrous effects of negative birth rates.

This is particularly concerning since South Korea isn’t a peaceful European nation surrounded by layers of other peaceful European nations like Czechia. Literally an artillery shell’s throw away from their capitol is North Korea. One of, if not the most heavily militarized nations on earth with an explicit ideological drive to liberate the South. I wonder how difficult it will be for North Korea to march across the DMZ when there’s 5% as many military aged men as there are now at the end of the century? I wonder how difficult it will be when their military aged men outnumber South Korea’s 1,000 to 1. (To be clear, North Korea’s fertility rate is estimated at ~1.8, so negative as well, but this can be considered replacement rate compared to the South.

So what are they doing to remedy this problem? Surely they recognize how bad things are when the fertility rate has dropped lower than anywhere else? Besides a lot of low-level policies that together might have some statistical effect but individually mean nothing, there’s the new planned capitol. Sejong City, built a few hours south of Seoul designed with families in mind, built from the ground up in an attempt to attract the exhausted government workers of Seoul to a more comfortable, affordable and family-friendly life. Unfortunately, at great expense, this city has had little effect. Boosting fertility from ~0.9 to ~1.1 (before dropping back below 1 again), major oversights like terrible public transport, people commuting 2 hours from Seoul to Sejong every day rather than actually living there, and a generally Seoul-less vibe of the city has prevented anything near the bump in fertility hoped for.

I guess South Korea will basically just cease to exist in a few generations? I have no proposed solution, but it definitely sucks.

3. The Solution Should Have Been 25 Years Ago

China went from the 1-child policy in 2016 to an explicitly pro-natalist policy in 2021. That’s quite a policy reversal in five years, and one must wonder what caused the fast change in sentiment. My guess is they realized how imminent population decline was, and how long population stabilization would actually take.

Just think about it for a moment. Any pro-fertility program would take time to conceive, implement and actually have an effect at encouraging people to make more children. Let’s keep it simple and say it’s just a $1,000/mo tax credit for anyone who has a child, and actually implementing this takes about a year. Then, a couple actually has to decide to make the baby (this takes about nine months if you weren’t aware), that child needs to grow, develop, be educated and finally enter the workforce. All this and you’re liable to need a full 25 years before a single joule of productivity is returned on that investment. If your problems are imminent, and your pension systems are already strained, having more children will only increase the overall dependency ratio (see earlier graph) in the short term, while not doing anything to help the problem for a quarter century.

Well this isn’t good.

4. Immigration

The 3 ton elephant-gorilla hybrid in the room. This is where discussions of a genuine issue often devolve into political drivel. Hopefully I can avoid that.

If breeding up new people takes too long, or is too difficult, the west has a relatively easy solution for bringing in working age people; open the doors, and let them in. The western world happens to be a lot more developed and comfortable than the developing world, and because of that, there are tens of millions of people living in developing countries who are more than happy to pick up their lives and move to a more prosperous and safe country. If these people are hard workers, and contribute more than they are given by the state, large numbers of immigrants could (theoretically) bring about a reduction of the old-age dependency ratio. This is a primary concern of an aging population, so solving the issue without any of the downsides mentioned earlier is extremely attractive.

Accepting large numbers of immigrants can certainly rebalance the dependency ratio. Immigrants are typically already of working age, and can be treated relatively less fairly than native-born citizens, as they aren’t given the same political rights, and have lower expectations when it comes to quality of life. This is even more true for illegal immigrants, who are often paid less than minimum wage, which generally benefits those hiring them through access to cheap labor. In theory at least importing large numbers of immigrants can keep population pyramids balanced.

The theory breaks down when encountering a generous welfare state, as is the case in most of Europe. When encountering access to welfare that enables free-riding, many immigrants would simply prefer not to work. After all, while living on welfare might be considered a relatively low-quality life for a native-born European, thus incentivizing work even if welfare is an option, it’s certainly an acceptable standard compared to war-torn Syria. I was astonished to learn that over half of Iraqi, Somalian and Afghani refugees to Finland still were not working after living in the country for a decade. Surely this sort of immigration will not work to solve the population crisis, and may actually strain the finances of the state even more than before.

In places like America, where the welfare system is tedious and bureaucratic, this is somewhat less of a concern. Illegal immigrant unemployment, while still more than the native-born population, is only so by a few percent. This makes perfect sense as illegal immigrants have real and significant disadvantages in the job market compared to citizens. Additionally, the concept of being “American” is not inherently tied to ones ancestry. Peoples descended from all parts of the world become American after a single generation, and many immigrants themselves identify primarily as American after permanently moving to the US (Musk comes to mind). Ethnostates like Germany, where there’s a dual meaning between german citizenship and german ancestry, is a much harder pill to swallow. An immigrant to Germany can become a german citizen, but they can never gain german ancestry, thus completely self-identifying as german becomes a near impossibility. Integration is much more difficult in nation states defined by an ethnicity when compared to the colonial states of America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

There’s also the cultural concerns I outlined in II, 2. Cultural competition between nations is one thing, but when your neighboring culture with a higher birthrate is literally your next door neighbor, the issue is a lot more personal. I won’t comment more on this aspect due to my inability to do so tastefully and without controversy, but there’s many right-wing bloggers and podcasters who are particularly obsessed with this aspect of the problem, and I’m sure if you’re reading this you know exactly what I’m talking about.

More Thoughts:

Won’t things even out after a few decades?

Unfortunately, the problem isn’t a temporary one. So long as populations are contracting, there will always be an excess of elderly compared to the young.

Whether society is down to its last 10 people with 4 of them being 64+ or the last ten million with four million being 64+, the burden on those of working age remains the same.

It’ll be a rough century, and unless we’re forward thinking enough not to worry about our own societal issues for the eventual remedy during our great grandchildren’s lifetimes, fertility is a very real concern.

Why does this seem to be a problem only conservatives care about?

As far as public debate on the topic, the people who seem to care about demographic collapse (in the West) are all very conservative. Viktor Orban, J.D. Vance, Musk, etc. all look at the population collapse as the existential risks facing civilization or at least one of the primary things we should care about. Why this is, isn’t exactly clear, but I think it’s mostly for aesthetic purposes.

The Fertility Crisis can be attributed to things that conservatives already cared about. The decline of the family, decreasing religious belief, acceptance of LGBTQ+, Feminism, Anti-natalist environmentalism, population replacement through immigration are all things conservatives didn’t like long before fertility became a serious issue. It just so happens that there’s a new problem that happens to have been caused by these things they already didn’t like. It’s too perfect of an opportunity to use the problem as justification for banning or minimizing the things conservatives already oppose.

“We aren’t supporting traditional family structures because we prefer them, we’re doing so because the existential risk of the fertility crisis is making us! Now get back in line.”

To be clear, I think this exact thing could be said about a lot of environmentalism. When a major problem comes along that happens to be solvable by doing what you really wanted to do already, the problem becomes a very useful view for convincing people to adhere to your preexisting ideology.

I suspect this makes it harder to actually deal with the problem itself.

I wish I was able to write posts as good as this...

Great post. You were able to organize thoughts that I've had in my mind for months very well.