Have you ever been stuck on a tarmac delayed plane? Last Friday, as I boarded my 7:00 flight to Miami I had no idea the torture I was in for. The next 6 hours of cramped seating, poor air conditioning, smelly neighbors, and boredom (my GOD the boredom) had me searching for something to do on my phone while waiting for a pilot that never came. Fortunately,

obliged me in some friendly (and not so friendly) discussion as to the efficacy of the Federal Reserve to alleviate my boredom.This culminated in me blocking him, him blocking me, and deleting all my comments (probably the only way he could actually harm me as the thoughts from our conversation are now lost). But now, as I sit waiting for my return flight to New York I’ve received the following text message…

So it begins...

Since debate about the Federal Reserve’s efficacy saved me from a slow death by boredom earlier this weekend, I hope writing about it might do me the same service today.

There’s a Conspiracy Afoot

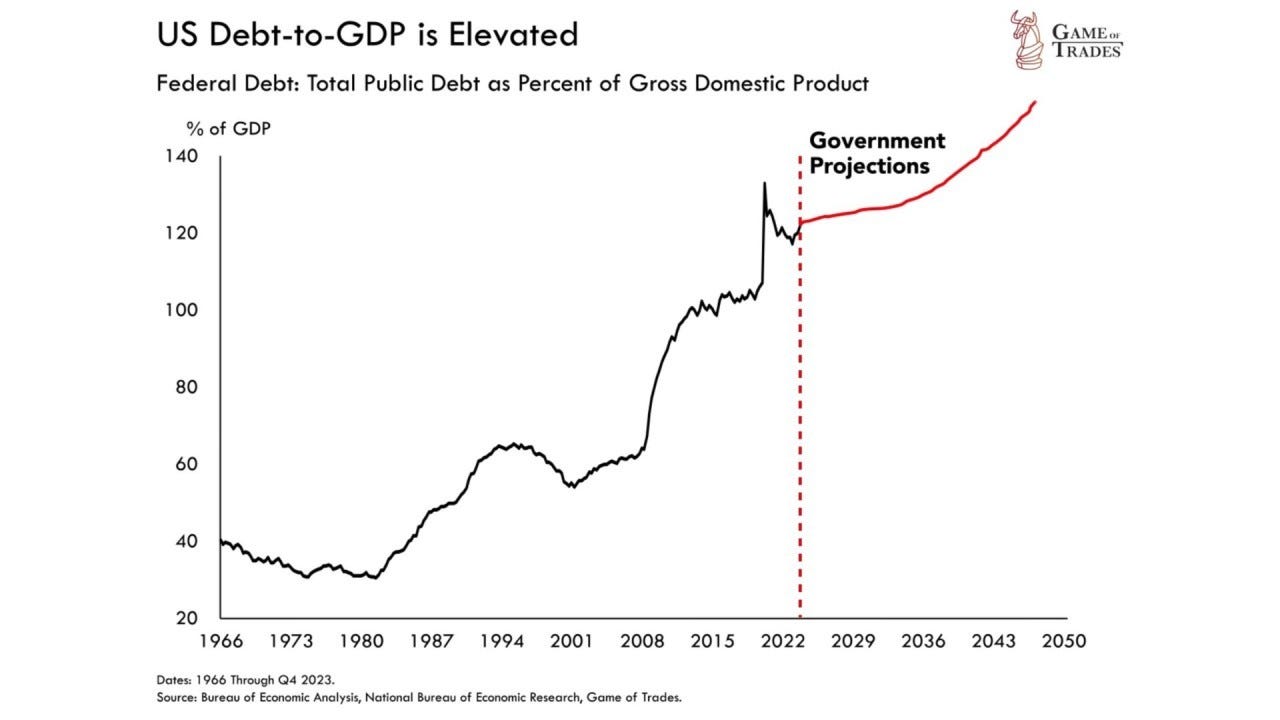

There seems to me to be a sickness of pseudo-economics going around. The Federal budget has truly ballooned out of proportion, reaching debt-to-GDP levels not seen since the United States just fought the largest war in human history. The importance of this all time high debt seems to have been lost on the voters and the people in charge, as the national debt is only the most important issue for 3% of American voters.

The cause of this situation can be clearly attributed to the largest line-items on the budget, a combination of various forms of welfare, and military spending. This situation isn’t helped by the most prominent global authorities on economics claiming the size of the debt doesn’t really matter, just the interest payments. Interest payments alone are on track to exceed $1 trillion this year, and in a decade, they could make up the entire federal deficit. The Fed is at the center of this, with the artificially low interest rates of the 2010s playing no small part in the massive expansion of the deficit. Central banks it seems, are riding us down the road to misery.

That’s the story they’ll tell you anyway. Yes, the deficit has never been larger, interest has never been more expensive, and the debt-to-GDP ratio has never been higher. But this post isn’t about the debt, the Fed, or the prophesied imminent default—it’s about those claiming that this system is on the verge of collapse.

Enter the Fed-skeptics, as I’ll now be calling them. These critics go to even greater lengths of delusion than the debt-ignorers. Claims that the Fed can’t literally affect interest rates, that the Fed is responsible for the debt, or that it’s just a bailout mechanism for the rich are thrown around like darts at a bar. This series was prompted by The Fed Is a False God, which I recommend you read for a great example of an incorrect Fed-skeptic, and more broadly a dissent against the Federal Reserve conspiracy theories that seem to pervade so many of the libertarian-minded.

We’ve got one side of the conversation that seems completely unconcerned with the debt, and the other making completely false claims about economics to discredit the Fed. There’s so much misinformation, that for most, it’s hard to actually understand what’s happening.

Fortunately, I’m here to cut through all the ignorance and get to the truth. I’ll be answering in a four part series;

The History of the Fed and Economic Theory

Are current levels of debt sustainable and if not, what are our options?

Who’s downplaying the risks of debt—and who’s spreading wild conspiracy theories about the Fed?

If you’re not already familiar with this topic, or loosely familiar, than this first post is for you. If you already know all about the Fed’s history, this first post is probably not for you. This is only part 1 of a 3 part series, so if the topic seems interesting but you aren’t interested in getting a refresh on the context, I recommend you subscribe and wait for the remaining two.

In this first post I’ll explain the history of the Fed.

In the future posts I’ll;

Part 2: Tools of the Fed and the four potential ways out of the current debt-crisis.

Part 3: Who are the Fed skeptics and why are they wrong? What should the role of the Fed be?

I. The History Of The Fed

1. Introduction To Central Banking

Central Banks were developed in the late 17th century in Sweden. From there, they spread across western Europe with the most notable example being The Bank of England which pioneered many modern banking practices. There was an undertone of promoting price stability and economic growth, but the primary purpose of these proto-central-banks were to serve the government’s interests. Paying for wars, founding colonies, financing secret police to oppress revolutionaries, and other, shall we say, government priorities. It wasn’t all bad, as they did serve to prevent a profligate monarch from debasing the currency, but these early banks certainly held few pretensions about serving the people, or even the economy as a whole.

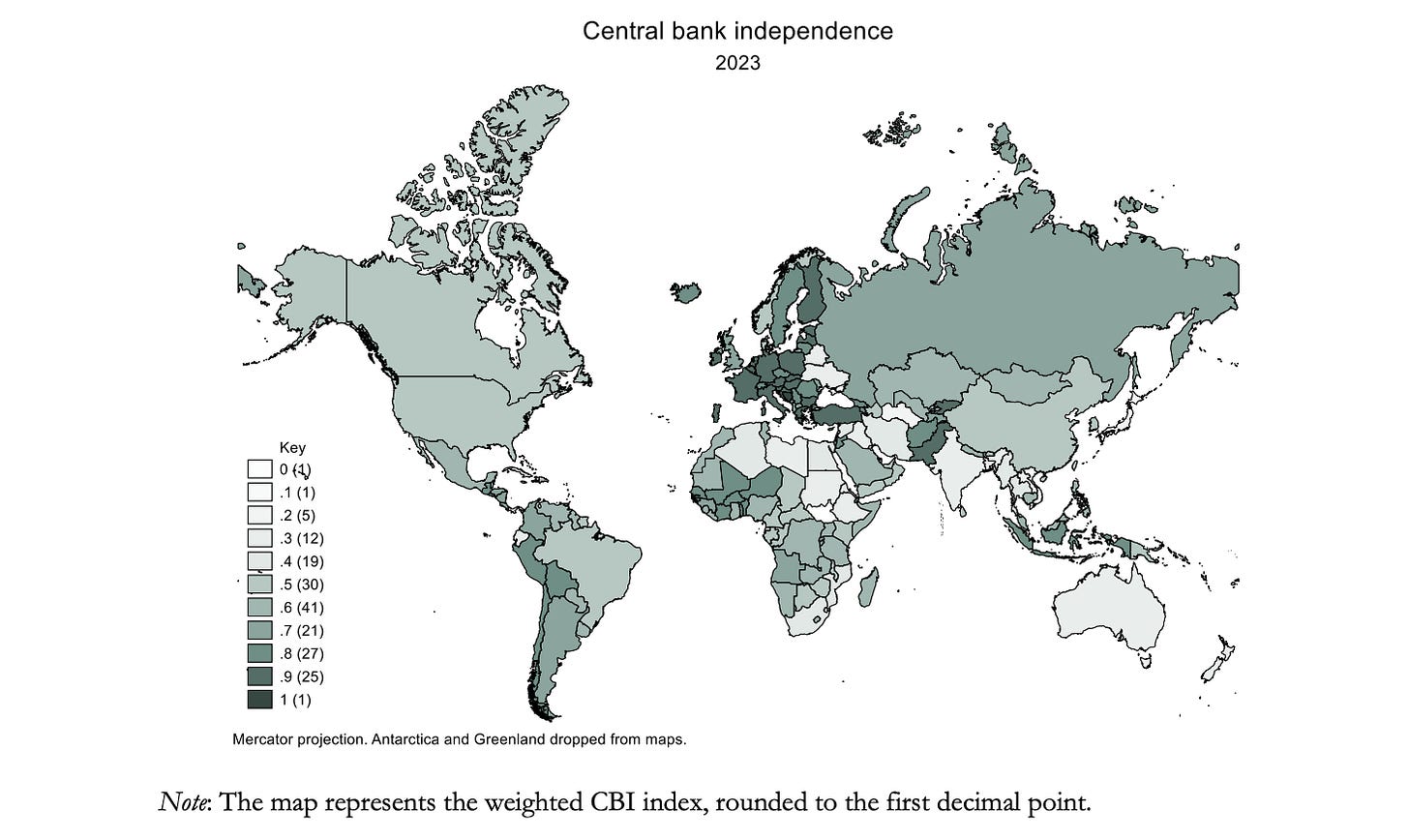

Let’s get the boring definitions out of the way. A Central Bank is an institution, usually established by the government, but sometimes by large banks, which is responsible for controlling the money supply and implementing monetary policy. In modern economies, they are often responsible for regulating the banking sector, and serving the lender of last resort by providing loans to banks during economic crises. They are sometimes mostly independent of the government, as is the case in Switzerland, or are mostly dependent on the whims of politicians as has been the case in Argentina.

Central banks are often given one or more mandates, such as Price Stability1 (Switzerland), Maximize Employment2 (USA), Financial Stability3 (UK), Economic Development4 (China), Exchange Rate Targeting5 (Hong Kong). Many countries also have a mixed mandate (Canada) or dual mandate (USA) where the central bank pursues more than one policy at the same time, which gets tricky, as pursuing one goal can lead to the detriment of another.

Central bank prudence does correlate with independence from politics, but there are many exceptions, and a completely independent central bank that is aiming towards infinite social welfare will probably perform worse than a completely dependent central bank that is focussed wholly on a currency peg. Argentina’s central bank, while theoretically independent, has long struggled with inflation due to political interference and broader economic mismanagement. In contrast, Vietnam, while less independent, has managed inflation effectively through its currency peg

This definition doesn't fully capture the varied roles of central banks throughout history or across different nations, as their goals and functions have continuously evolved. However, it provides a solid foundation for understanding how central banks have developed, and we can build on this to develop a full understanding.

2. The Road to a Central Bank in the United States

1791–1811 / The First Go Around

The First Bank of The United States looked nothing like a modern central bank. They couldn’t set monetary policy, regulate private banks, set reserve requirements, or act as a lender of last resort. While the First Bank didn’t have anywhere near the authority of modern central banks, it did more than a typical commercial bank. It had the unique power to operate across state lines, issue a stable national currency, and provide essential loans to the government during its time of extreme need.

Alexander Hamilton (yes, that Hamilton), a staunch advocate for a strong central government, saw the bank as critical for establishing financial credibility for the young nation and ensuring economic growth through centralized control over credit and currency. However, the bank faced fierce opposition, particularly from figures like Thomas Jefferson, who feared it would concentrate too much financial power in the hands of the federal government and infringe on states’ rights. Keep this in mind, as this disagreement will be a running theme throughout this history.

Ultimately, this first central bank was necessary to prevent government default and rampant inflation due to the significant revolutionary war debt. It turns out that cutting all trade with your recent overlord and largest trade partner, who proceeded to blockade and invade you, isn’t good for the economy. (Who knew?) This first attempt at a central bank was short lived, and was liquidated at the end of its 20 year charter having served its purpose of preventing government default.

1816–1836 / Second Time’s The Charm

Aptly named The Second Bank of the United States vindicated the saying “History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes”. It was charted immediately following the disastrous war of 1812. Who knew that declaring war on your largest trade partner, who proceeds to blockade and invade you, isn’t good for the economy? I’m starting to see a pattern. Anyway, just like last time, despite significant opposition (and largely thanks to the Supreme Court ruling it constitutional) desperation prevailed. With a slightly expanded mandate from its predecessor, it ran its course, stabilized the economy and wasn’t renewed by Andrew Jackson (yes, that Andrew Jackson) at the end of its charter.

Contrary to how many people see central banks today (Money Printer go Brrrr), the second bank did a good job of reducing inflation, primarily by taking away control from the states on how much debt they could issue. Prior to the second bank, states were essentially unlimited in the amount of debt they could issue, and since they became no longer self-regulated, austerity had prevailed. As you know this was short lived though, setting the stage for the subsequent banking troubles.

As an aside, Charles Dickens, visiting Philadelphia in the wake of the bank’s closure, remarked on the gloom that seemed to have settled over the city, a reflection of the economic anxiety caused by the bank’s abrupt end;

The stoppage of this bank, with all its ruinous consequences, had cast (as I was told on every side) a gloom on Philadelphia, under the depressing effect of which it yet laboured. It certainly did seem rather dull and out of spirits.

1837–1863 / Free For All

It turns out, if you thought one central bank was bad, try dozens all doing their own thing.

Classified The Free Banking Era by historians, the end of the second bank led to monetary anarchy. Rather than a single national bank being responsible for regulating currencies, each state chartered its own independent banks, which operated without a national oversight system. No less than a third of banks failed during this period, wiping out individual savings and leading to widespread economic uncertainty. This was a period of significant economic and national growth, but the numerous runs on banks during this period and hundreds of instances of Wildcat Banking (basically crypto scams before they were cool) led to significant decline in trust in banks. In an environment of few regulations, it was easy—and tempting—for banks to speculate heavily on railroads. When the inevitable overcapitalization led to a market crash, it was usually the consumers, who’s money the banks were gambling with, that were left holding the bag.

1863–1907 / Third Time’s The Charm?

The fragmented system of regional and state banks wasn’t working well for the country. This time, what was left of the Union wasn’t ready to wait around until after the war to nearly go bankrupt. During the American Civil War, economic desperation served yet again to force action, and in 1863 Lincoln signed the National Currency Act. Rhyming the first two national banks, the act established a national currency backed by federal bonds and created a network of national banks that fell under federal oversight, replacing the chaotic mix of state currencies.

The establishment of these banks saved the Union from insolvency, while also laying the groundwork to prevent the freebooting behavior of the previous era. This was the birth of modern US central banking, as it stills serves as the governing framework (albeit with heavy amendment) today. Though there was still no central bank as we know it, the increased federal oversight of regional and state banks laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the Federal Reserve system.

1907–1913 / Central Banking Takes Hold

According to the long standing tradition of speculating on risky assets, Americans were riding high in the spring of 1906. The banking sector was at an all time high, after strong economic growth, combined with increasing trust in banks, led to a vast growth in deposits. That was until an attempt to corner the market of the United Copper Company led to a major default and a decline in asset prices. People willing to purchase shares at their inflated prices dried up, leading to a Liquidity Crisis, a situation where people had valuable assets on paper but couldn’t sell them fast enough to pay off debts, which triggered defaults.

Imagine you’re at an auction and you’ve collected a bunch of rare, valuable paintings. You’re feeling great because, on paper, these paintings are worth a fortune, and you know you could sell them for a huge profit. But suddenly, rumors spread that the auction house is going out of business, and everyone panics.

No one is willing to buy paintings anymore because they’re all too busy trying to sell their own. So, even though your paintings are valuable, you can’t find anyone to buy them, and you still have bills to pay. You’re “rich” in paintings, but you’re broke when it comes to cash.

That’s the liquidity crisis: when people have valuable assets, but few are willing to buy them, leaving them without the cash they need to pay off their debts. To stop this crisis from unnecessarily getting even worse than it already was, the government stepped in.

And by stepped in, I mean they bravely announced they were unable to help, and begged J.P. Morgan to step in and fix the problem. Morgan was rich, and by rich I don’t mean it in the sense we call billionaires like Musk and Bezos rich, who’s assets are tied up in the value of companies. Unlike them, he was extremely capital rich, being the controller of one of the nations largest banks with an immense personal fortune. Still, even he couldn’t resolve it alone. It took dozens of smaller financiers, injecting liquidity into the market, to keep things from spiraling further. In fact, they even called upon clergy to preach market confidence.

Eventually the crisis resolved, but never before had the financial markets been so shaken. The crash was driven not just by overvalued assets but by a sharp swing in confidence. As trust in banks collapsed, people rushed to withdraw their savings, causing a chain reaction of defaults—a classic negative feedback loop. If you hear your neighbors bank just defaulted, and his entire savings evaporated, you’re going to get your money out of the system as quickly as possible, causing your bank to default, causing your other neighbor to panic, and so on and so forth.

Both the government, and the bankers agreed that something needed to be done. In a modern economy, debt and assets are held in an interconnected web, and during a panic defaulting borrowers tended to reinforce rather than dissipate their effects. This marked a major shift in thinking: a central bank as a Lender of Last Resort could step in to inject liquidity into the system during crises, preventing smaller banks from collapsing and stabilizing the broader economy. Essentially, banks were to be established that had the authority to issue currency during a crisis. This of course wasn’t without controversy, as an economic safety net might encourage market players to make riskier decisions.

3. Establishment and Early Years of the Federal Reserve

As an early Christmas gift to the country, on December 23rd, 1913, president Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law. Its goals were essentially as follows;

Establish more effective supervision of banking in the United States.

Create a central bank to conduct monetary policy and;

Provide necessary liquidity during a financial crisis.

This wasn’t anything unprecedented, as our European cousins had been operating central banks with similar goals for hundreds of years at this point, and for many, it was seen as long overdue.

The Federal Reserve was structured around a seven-member Board of Governors based in Washington, D.C., appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. This board was responsible for overseeing the system and setting national monetary policy. Alongside the board were 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, each serving a specific geographic area of the country. These regional banks acted as the operational arms of the Federal Reserve, implementing the policies set by the Board of Governors.

Each of these regional banks was partly owned by private member banks in their respective regions, which held stock in the regional Fed banks. However, this stock ownership did not function like typical corporate stock ownership—it didn’t confer control but did ensure a degree of alignment between the interests of private banks and the broader economy. The idea was that this structure would blend public and private interests to create a more stable and flexible system.

In theory, this would help prevent future liquidity crises, promote price stability, and support the overall economy.

An interesting consequence of this original map is that these districts haven’t changed in over a hundred years. As populations have grown in different areas, relatively unimportant (economically speaking) areas of the country like the fourth district have equal standing with the twelfth district, which represents the entire west coast.

1914 - 1929 Coasting on Momentum

This time, the United States wasn’t going to be bankrupted by a major war. The Great War, fought mostly between the European powers had millions of young men flocking to the fields of France, where they were summarily shot, blown up, gassed and bayonetted. When you’re getting shot, you aren’t producing much for the economy, and those who were left to work were too busy producing munitions to make much for the consumer markets. All of a sudden, the food and industrial goods that war-free America was producing were in high demand, and the Europeans were willing to pay. American loaned billions to the European powers that went right back into buying American goods. It was essentially a U.S. jobs and stimulus program, with Europe footing the bill.

After most of the hard fighting had been done, and everyone was thoroughly exhausted, the United States joined in 1917, helping to tip the balance in the final year of the war. The U.S. got a seat at the peace table, along with the prestige, gratitude, and influence that went along with it. As a result, by the 1920s, the United States was in the strongest economic and political situation of perhaps any country ever, and it was its turn to reap the rewards.

The roaring 20s were called that for a reason. Although there was some inflation and the occasional economic shock, the economy was on a sustained bull run. The central bank had little to do. It’s hard to credit the system set up after the crash of 1907 with anything significant during this period, as there were too many other factors driving the economy for their influence to be necessary. However, the Fed’s easy money policies—keeping interest rates low—helped fuel speculative bubbles in real estate and the stock market, which would soon lead to trouble.

The 1929 Crash

They say that the route of all evil is the love of money, and there’s no sweeter money than that which comes easy and free. Prior to the crash, anyone could become a Wall Street millionaire by taking a stock tip from a stranger, borrowing more money than they could ever repay at absurd interest rates, and buying in. Easy come, easy go—and just as some made millions on borrowed cash, many more lost it. Stocks go up and down, but your bank or loan shark doesn’t care if you blew their loan on Dogecoin and NFTs—the amount owed stays the same.

The specter of speculation was the sickness, and it was the Fed’s time to shine. They hadn’t yet had a chance to show their value to the country—things had been going too well for too long—and by golly, were they going to save the day now that they had the chance! Seeing speculation as the root cause, they decided the best way to get through the economic slump was to curb it. Interest rates were raised to make borrowing for speculation far less attractive, and the worse things got, the tighter they squeezed.

Raising interest rates had the effect of contracting the money supply. As people moved their money into high-interest government bonds and the Fed continued to raise rates, the amount of money freely circulating in the economy shrank. This caused another liquidity crisis, this time on a larger scale, driven by rational preference for safer investments rather than irrational panic. The result was significant deflation, which would soon have devastating consequences.

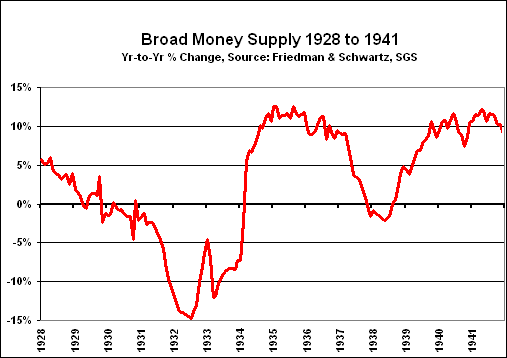

Money supply 1928-1941

You might be thinking, “Deflation doesn’t sound so bad, right?” Instead of prices going up every day with inflation, they go down, meaning your buying power increases. Sounds great? Not so fast. While inflation has its downsides, deflation can be much worse.

The problem with deflation is twofold. First, while it benefits lenders and savers, it places a heavy burden on borrowers. If inflation causes a lender to lose 5% of a loan's value, that’s not ideal, but they still have an asset worth 95% of its starting price (plus interest). Meanwhile, the borrower’s debt is easier to pay off. But with 5% deflation, the opposite happens—the borrower’s debt burden increases, pushing them toward default. This leaves one party bankrupt and the other holding useless bonds. Imagine if the value of your house dropped by 5% every year while your mortgage stayed the same. Your million dollar house would be worth tens of thousands by the time you retired, all the while you would be paying back the original million dollar mortgage.

Second, deflation discourages investment and spending. If your million-dollar bank account is being inflated away by 5% a year, you’re going to be eager to put that money to work—invest it, lend it, or spend it now rather than later. But if your bank account (or dollars hidden in a safe) is gaining 5% every year with zero risk, you’re far less motivated to invest or lend. The bar for what counts as a “good investment” gets much higher, and holding onto your money becomes more attractive than taking risks.

This is called a Deflationary Spiral—and it’s the kind of nightmare that keeps central bankers like Jerome Powell up at night. While inflation can at least encourage spending, deflation drags the entire economy down, with little benefit to anyone.

II. The Schools Of Economic Thought

Economics Isn’t A Science

This is probably a good time to talk about the problem with economics, especially macroeconomics. It’s not a science. Sure, economists come up with theories, with some very intelligent sounding justifications for those theories, and see what happens when countries adopt those theories. For basic concepts, like establishing property rights and creation of a currency, economic theory works well because the cause-and-effect relationship is more obvious, and the correlation is much stronger. But for more complex questions. When it comes to more complicated questions like what level of debt is sustainable, what level of inflation is acceptable, or what percent banks should set interest rates, the causes and effects are so loosely correlated that there isn’t much room to establish causality.

For instance, the Phillips Curve, which posited a stable inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment was widely accepted as it seemed to work for a while. This of course fell apart in the 1970s during stagflation where there was high inflation and unemployment simultaneously. The inverse relationship turned out to be coincidental, or both based off some additional factors that weren’t being accounted for. Some economists, such as Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, openly acknowledge that economics is more about “narratives” or “interpretations” than hard, scientific facts. These narratives are important, but they are not laws of nature like gravity—they change as the world changes.

Thus, economics is not really a science in the strict sense—more like two people in a trench coat pretending to be one, sneaking into the movie theater alongside the other hard sciences. It uses intelligent-sounding theories, but struggles to establish the same kind of clear, testable causality as fields like physics or chemistry. Even the Nobel Prize in Economics isn't technically a Nobel Prize—it was created by the Bank of Sweden nearly a century after Nobel’s death in the late 1960s, though the public often sees it as equivalent to the other sciences’ prizes.

The fundamental problem is that it’s almost impossible to run macroeconomic experiments. We can’t recreate the Great Depression without a decade of artificially low interest rates, nor can we see what would have happened without a central bank at all. Scott Alexander recently gave a semi-satirical twist on the simulation hypothesis. If it’s true that our entire world is being simulated, my theory is it’s done just an elaborate economic simulation.

But just because economics isn’t a science in the strictest sense does not mean it’s useless. Without economic theory, we’d have no framework for evaluating policies like corporate taxes or the Fed’s actions. Economics gives us a way to argue that high corporate taxes might drive businesses offshore or that Fed intervention is—or isn’t—justified.

So although there’s little or no opportunity to test the theories pushed by different schools of economic thought, there are better and worse economic policies. There’s agreement that triple digit inflation is bad, that free markets are more efficient than centrally planned economies and that not all externalities are captured in an economic transaction. The debate between might seem heated, but in truth the reason it’s possible for antithetical economic theories to exist at the same time in intelligent minds is that their predictions are largely similar.

Of course, the devil is in the details. Let’s look at the different analysis of the Great Depression to start to understand the differences;

Since we’re talking about the depression anyway, I think it’s a great opportunity to explain what the four different schools of economic thought are, and what they have to say about it. A practical example is easier to contend with than pure theory, and although not all of these theories existed in 1929, they all have thoughts and theories about what happened, and what might have happened otherwise if different action was taken.

It will be important to remember that these theories aren’t mutually exclusive. Classical Economics is the predecessor to the other three, and despite making separate claims Austrian and Keynesian Economics borrow a lot from each other. Developments of the Classical School serve as the basis for the Austrian School which serves as the basis to the Keynesian School. The picture is ultimately more complicated than I am explaining here, so remember that I’ll primarily be talking about the unique aspects of each, while ignoring their significant similarities.

Classical Economics

This is the classic free market capitalism that we know and love. Adam Smith’s invisible hand put into words what groups of people trading goods and services knew all along. Individuals pursuing their own self interest, combined with trade naturally causes people to find ways of benefiting each other. Absent the use of force, the only way to convince people to sell you their products or labor, is by accumulating something that they will accept in return. The only way you can do that is by selling your products or labor to others, and in this way in serving your own self interest, you are motivated to serve others. The more you wish from others, the more you have to serve them.

The greatest insight we gained from classical economics is that Markets Are Efficient. This was intuitively understood beforehand, but prior to making this explicit, the obvious path to increased economic growth was through control. As state capacity increased, an understanding that markets themselves are desirable and shouldn’t be disrupted without good reason served as a check on economic their increased capacity for economic meddling.

The Labour Theory of Value, the theory that the value of a good is determined by the amount of labor required to produce it. The labor that went into producing a good is essentially the cost of production in a capital light society like the 17th century, so this theory was quite reasonable at the time. As technology developed and the tools we use became more important than the labor that went into them, labor declined in importance relative to capital. The labour theory of value became less useful.

Think of almost fully automated factories producing cars or gigantic combines harvesting 1,000x what a single farmer with a scythe could. For these means of production, labor is a very small portion of the overall cost of production. The classical economic theories thus weren’t perfect, but they were innovative for the time and laid the groundwork for many of the assumptions of modern economics.

Classical Economics would have little to say on the great depression, as the theory is too basic to recommend against or for central bank action. It does little to suggest anything to mitigate financial crisis, and would take further development to do anything of the sort.

Austrian Economics

Austrian Economics arose in 1871 with Carl Menger’s book Principles of Economics. Serving as a sort of improved classical economics, it retained most of the support of free markets, but replaced the labor theory of value with the Marginal Theory of Value. This new theory claimed that the value of goods is subjective and determined by individual preferences. I could work for a hundred hours taking apples and dough and turning them into an apple pie, but my apple pie would be able to sell for a lot less than the most skilled chef spending an hour doing the same. Despite significantly more labor going into my apple pie than his, the market places more value on his product than mine. This development was fundamentally necessary, as the 19th century saw a truly astonishing increase in capital and labor expertise in Europe, meaning the labor theory of value was already starting to break down.

There’s not much in economics that is empirical, but as far as determining of a good or service in a free and frictionless market, this is about as close as it gets. Of course thinkers like Marx retained the labor theory of value, which I suspect is part of the reason communist economies end up so capital poor.

More recently, Austrian Economics has been picked up by thinkers like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises who’s developments can be better characterized as being in opposition to collectivist economic systems, opposition to central banks, and identification of the business cycle. The crux of this theory is that markets are efficient, government intervention or control of markets is inefficient and leads to inferior outcomes, and that markets naturally rise and fall over periods of years. These theories served to justify capitalism at a time when socialist economic principles were at their peak. It might seem ridiculous in the modern day, but in the early 20th century, it seemed a real possibility that socialist revolutionaries would sweep across the world and end capitalism. Thus, besides the identification of the business cycle, the further developments of Austrian Economics can be seen as in opposition to collectivist systems.

The Austrian School looks at the great depression as an example of failed monetary policy. The Federal Reserve had kept interest rates artificially low for years, and since there’s no such thing as a free lunch, the Great Depression was a natural reaction to this poor monetary policy. The cycles of boom and bust are a natural part of the economy, but the increased boom in the 20s was the direct cause of the stronger bust in the 30s. The central bank policy afterwards was even worse according to this theory, as the best thing to do would have been to allow the market to self-correct, then run without intervention going forward.

Keynesian Economics

Keynesian economics can best be contextualized as a response to Laissez-Faire principles first support by Classical Economics, then the Austrian School. John Maynard Keynes in his 1936 work The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money suggested that government could strategically intervene in the economy, especially during times of economic crisis to stabilize the economy and ensure higher employment. To be clear this wasn’t a complete reimagining of markets and their forces as is the case with Marx, but a tweak on the already existing free market paradigm to ensure better outcomes were achieved over the long run.

The core of the theory is that economic crisis, while still part of the business cycle are largely crisis of demand. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with the productive forces of the economy, but in the absence of enough buyers for their product, as happens occasionally, they can be forced to shut down completely, which has further negative shocks throughout the economy. Under these conditions, free markets alone will not be effective at restoring full employment and market stability during and after a crisis.

Aggregate Demand refers to the total quantity of goods and services demanded across all sectors of an economy at a given overall price level and within a specified period. It represents the sum of spending by households, businesses, the government, and foreign buyers on an economy’s goods and services. This being the driving force in the economy, a decline in aggregate demand leads to crisis. This was a major innovation, as it was contrary to the classical principle that supply created its own demand.

Another concept, and tacit justification for government spending was The Multiplier Effect. This refers to how each dollar of government spending generates more than a dollar in economic output, because the recipients of government spending (like contractors, workers, etc.) will spend their income, generating further rounds of consumption. Additionally, governments can spend on traditionally economically unjustifiable projects like infrastructure, education and healthcare, so the economy as a whole can benefit in the long run. Perhaps there’s no economically justifiable reason to send poor children to school in a free market, but if a more educated populace leads to higher productivity, and thus more wealth, this government spending can have a multiplicative effect on the overall economy where the private sector usually can’t.

Classical economists view that eventually markets would correct themselves may very well be true. Keynes famous quote “In the long run, we are all dead” exemplifies his view that although markets may be self correcting, and government stimulation of demand through deficit spending isn’t necessary, if we can engineer a faster recovery from economic crisis, then we should.

Keynesian Economics can be seen as a direct response to the depression and the poor government response to it, especially given the context of when his seminal work was published. Roosevelt’s New Deal was a mixture of fiscal policy interventions, but the largest Keynesian stimulus was actually through World War II spending, rather than strictly through the New Deal programs. According to Keynes, rather than stimulating the economy with spending during the crisis, the constrictive action of the Fed after the depression led to an even further decline in demand, increasing the crisis. The government should have increased spending and reduced interest rates to stimulate demand, and in theory this would have prevented the failure of so many businesses that characterized the depression. The success of WW2 spending, along with the New Deal served as evidence for the success of the theory, as recovery from the depression went along with an expansion of government spending.

Monetarism

While Keynes theories can largely be considered a theory of fiscal (government) policy, Milton Friedman’s theory of Monetarism (1956) was one of monetary (central bank) policy. Rather than focussing on the role of demand, monetarists argue that the total amount of money in an economy, The Money Supply, is the most significant determinant of economic performance, particularly the rate of inflation. This is largely the view that predominates the Feds policy right now, so we’ll go into a deeper explanation of this later, but it’s important to get a brief introduction since we’re already comparing different theories.

Standing as a sort of middle ground between Keynes and the Austrian school, it eschews government spending during a crisis in favor of expansion of the money supply through Central Bank Action. Monetarism aligns with Austrian thought on the dangers of government spending, but it uses central banking as a tool for price stability, which the Austrian school opposes. It sees price stability, as in no significant deflation or inflation as the primary goal of the central bank.

The most important development of Friedman was the Quantity Theory of Money which (without boring you with the equations) claimed that price levels and the overall money supply are related, and thus to target consistent price levels, central banks should manipulate the money supply. When there is too much money chasing too few goods, this drives up prices, hence the need to regulate the money supply carefully. To be clear, increasing the total money supply is necessary when there’s economic growth, so a continuous expansion of the money supply in line with economic growth was a key aspect of price stability under this view.

Remember this graph from earlier? Monetarist see the significant decline in the money supply as the primary cause of the depression, and the subsequent expansion as the remedy in the mid 1930’s. Ideally of course there would not have been the deflation ahead of time, but the monetarist critique would largely be on the central bank’s failure to inject money into the economy when it was most needed.

Monetarist have an important part to play in central bank history, and laid the groundwork for the theories that underlie modern central banks, however eventually it was realized that manipulating the money supply in an intentional way isn’t as simple as equations might make it seem. As financial instruments became more complex in the 1980s, it became increasingly difficult to measure and control the money supply precisely, leading central banks to shift towards targeting interest rates instead.

There’s one more theory that I’m not mentioning here, and it’s most relevant for the current debate around the Fed, but I’ll leave that for the last section, 5. Modern Monetary Theory, as it has the most bearing on my next post. For now, let’s return back to the history.

4. The Great Depression To The Modern Day

The Great Depression Response (1936-1973)

Over 9,000 banks failed during the great depression. By far the largest drop in economic prosperity the United States had ever seen. This set off a lot of alarm bells in government, and there was a general consensus that something needed to be done to ensure this never happened again. Focus was again on the Fed, and the thousands of banks that had been foolishly speculating with consumers savings. While people still agreed that banks should be able to invest the money they hold, it was clear that limits needed to be imposed on banks to ensure that they would not be as vulnerable to failure.

The government responded with The Glass-Steagall Act (1933). This provided for the separation of commercial and investment banking (no more rampant speculation with consumers life savings) and expanded the Fed’s ability to respond to a crisis, while centralizing authority to ensure uniform policy decisions were made between the various regional banks. Prior to this the various regional banks were enacting different responses to the crisis, which caused a lot of their efforts to cancel each other out. This also created the FDIC, which was insurance that gave people confidence that even if a bank failed, their deposits would be paid by the government. This dramatically reduced the number of bank runs.

The re-expansion of the money supply was crucial in fighting deflation, one of the major issues of the early 1930s. This, combined with government spending through the New Deal, helped stimulate demand and restore economic activity, although at a heavy cost in the form of increased government debt. Eventually recovery happened, but as said before there is significant debate as to what actually caused this recovery. here’s considerable debate over what drove the recovery, with Austrian economists attributing it to natural economic healing, Monetarists crediting the central bank, and Keynesians pointing to government spending. Most likely, it was a combination of all three forces working together. The economy was naturally recovering, expansion of government spending stimulated demand, and a loosening of Fed policy did the same.

During World War 2, the Fed worked closely with the United States government to ensure enough money was available to pay for the war. There was a sharp expansion in the money supply during this time, as loans were given en-masse to the government in order to pay suppliers and contractors for the tools necessary to win the war, which led to inflation. No one was necessarily surprised by this, as it was seen as a necessary cost in order to win the war.

After WWII, the U.S. entered a golden age of economic growth fueled by strong consumer demand, government investments like the GI Bill, and America's dominance in global manufacturing. The Fed played a relatively passive role during this period, as economic expansion proceeded with minimal intervention. Thus the actions of the Fed during this time aren’t very interesting. That is until the multiple Oil Crisis in the 1970s.

The 1970s In Crisis (1973-1979)

By the late 1970s, the United States had become highly dependent on oil, which was seen as an overwhelmingly positive force at the time. Cheap and energy-dense, oil powered unprecedented economic growth. However, this heavy reliance on oil, particularly foreign oil, would soon become a major vulnerability. Almost every adult American had a car, and even the way we make cities was redesigned around this amazing invention. There was basically no downsides to oil consumption, and as demand around the world increased, the United States grew ever stronger.

That was until 1973. Egypt and Syria launched an attack against Israel to recover land they had lost a few years earlier (and maybe more) which later became known as the Yom Kippur War. A western supported Israel was yet again beating the Arabs, and doing so to an extreme extent, which caused a lot of neighboring Arab nations to find a problem with that western support. OAPEC, and organization of Arab oil producing countries decided that enough was enough, and they just so happened to be some of the worlds leading producers of Oil, so they announced an embargo.

This was the beginning of the 1973 oil crisis. Literally overnight, the price of oil nearly tripled. As energy is one of the fundamental inputs for goods, from manufacturing to transportation, this caused severe shocks across the global economy. This sudden price shock caused stagflation—a rare economic condition in which inflation soared while economic growth stagnated. Businesses faced higher input costs, which they passed on to consumers, while demand fell, causing a recession.

Paul Volcker was appointed as Fed Chairman in 1979 largely due to his reputation as a monetarist committed to controlling inflation at all costs. His approach was in stark contrast to the more accommodative monetary policies of his predecessors. In the same year, the Iranian revolution led to Iran embargoing the west under its new Islamist government, largely for the same reasons as last time, sending oil prices sky-high globally. Volcker raised interest rates dramatically, which led to an economic slump. The theory went that a short term recession to get inflation under control would lead to long term stability. Volcker implemented strict monetarist policies, aiming to reduce inflation by controlling the growth of the money supply. By drastically raising interest rates, he curtailed borrowing and spending, which eventually brought inflation down but at the cost of a severe recession.

Volcker was the strongest proponent of Monetarism, which I’ve outlined earlier. Under monetarist theory, the cause of inflation is primarily too much money chasing too few goods, which has proven to be useful when dealing with government deficits, printing large amounts of money, or other methods of increasing the money supply. What monetarist theory is not well-suited for is cost-push inflation, or the inflation that occurs when the fundamental costs of goods rise due to supply side shocks. As was the case in the 1970s, where the price of energy and oil rapidly increase, the cause of inflation wasn’t on the too much money side of the equation, but on the too few goods side of the equation. Monetarist policy did indeed bring inflation under control, but the sustained economic crisis of the 1970s may not have been worth it.

Alan Greenspan (1987-2006)

Volcker was eventually able to get inflation under control, partly due to tight economic policy and partly due to normalizing oil prices, but the damage was done. Monetarist theory fell out of favor in the halls of Washington, and it was time for a change.

In response to the 1987 stock market crash, Alan Greenspan was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve. A close associate of Ayn Rand, and strong proponent of the self-correcting nature of free markets, he was a pragmatist, willing to take different aspects of different economic theories to suit the conditions of the economy. He was not completely laissez-faire though, he did acknowledge the importance of monetary policy in keeping price stability through setting interest rates, while believing that the economy would take care of economic growth and productivity itself.

Greenspan kept inflation low throughout his tenure and managed interest rates carefully, contributing to what became known as the Great Moderation, a period of economic stability and growth. Whether this growth was primarily due to his policies or external factors, such as the rise of the internet and globalization, is still debated. It’s undeniable that this was a time of significant economic growth, and for most of his tenure, the national debt and balance sheet of the Fed remained stable.

An important influence of this time was congress repealing the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999. This removed the barrier between commercial and investment banking, as well as many of the regulations applied to banking. There hadn’t been a bank run in over half a century by then, and it is undeniable that restrictions on what banks can invest in creates a less efficient economy, so this was not a wholly irrational move. (Remember this for later)

Toward the end of his career, particularly after the 2008 financial crisis, Greenspan reassessed his earlier belief in the self-regulating nature of markets. In his testimony before Congress in 2008, he admitted that he had 'found a flaw' in his ideology, acknowledging that markets might not always behave rationally and may require more oversight. While Greenspan is credited with maintaining economic stability and low inflation during his tenure, his policies of deregulation and low interest rates also contributed to speculative bubbles, including the Dot-Com bubble and, later, the housing bubble, which would play a significant role in the 2008 financial crisis.

The Great Financial Crisis (2007-Present)

If you were reflecting on the previous twenty years of economic growth in early 2007, it seemed that a responsibly managed central bank actually did serve to keep down inflation, and keep economic growth humming along. While the U.S. economy experienced strong recoveries from downturns during Greenspan’s tenure, the seeds of the Great Financial Crisis were sown during this period. Deregulation of the financial sector and low interest rates encouraged excessive risk-taking, particularly in the housing market, creating hidden vulnerabilities beneath the surface.

With the deregulation of commercial banks, the ever-present temptation to speculation with other people’s money reared its ugly head. Banks still had to keep an heir of responsibility though, so rather than jumping at every hype-bubble the market provided, banks slowly increased their holdings of (in theory) financially sound mortgages. At first this was fine, as the traditionally methods of assessing a borrowers likelihood of default were enough to ensure that the mortgages banks were lending out were safe, but as the demand for high-yield, low-risk investments grew, the standards for these mortgages began to drop.

Through complicated financial instruments that are beyond the scope of this essay, banks were lending out money to borrowers who had a significant likelihood of default. Banks bundled thousands of mortgages into mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which were sold to investors. These securities in theory would be a combination of highly safe loans (from those who had a secure job, assets and good credit) with a small percentage of riskier loans. These securities were then further divided and packaged into collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), with credit rating agencies giving them high ratings, despite their risky underlying assets. This gave the illusion of security, even as the risk of default grew. Unfortunately, due to the complicated nature of these securities, no one really knew the quality of the securities they held, blindly trusting the credit rating agencies false ratings.

As it became clear that the housing market was collapsing and these securities were overvalued, a chain reaction ensued. Lehman Brothers—one of the largest financial institutions in the world—declared bankruptcy in 2008, triggering widespread panic across global financial markets. Major banks faced insolvency as their assets were revealed to be worth far less than their debts.

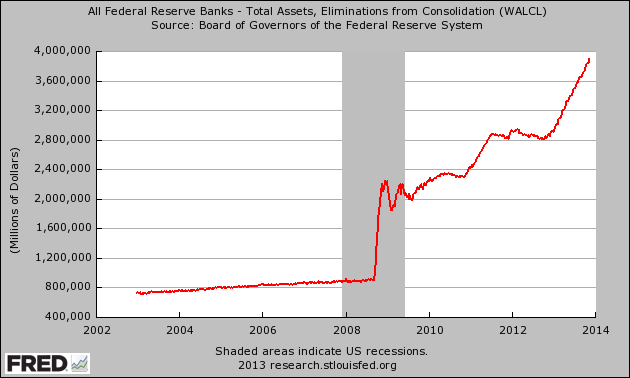

To stabilize the financial system, the Fed under Ben Bernanke implemented Quantitative Easing (QE), an unconventional policy where the central bank purchased large amounts of government bonds and mortgage-backed securities to inject liquidity into the economy. This aimed to lower long-term interest rates and encourage investment.

The markets weren’t the only ones suffering, as GDP contracted, unemployment rose, housing prices plummeted and debts skyrocketed across the economy. While the Fed can theoretically set interest rates below zero to stimulate the economy further (Many European countries did this), the Fed instead directly intervened in different financial markets, purchasing securities to stabilize the economy. They were not keen on allowing the country to fall into another Great Depression, but this did not come without cost. Both the government debt, and the Feds balance sheet expanded, dramatically during this time.

Ultimately, the financial crisis led to a rethinking of economic policy. Keynesian economics, with its emphasis on government intervention, gained renewed attention, while Austrian Economics, which Greenspan had championed, was discredited in the eyes of many policymakers. The crisis also sparked debate about the need for greater regulation of financial markets and the limits of relying solely on central bank monetary policy to stabilize the economy.

Modern Monetary Theory

In the gap left by Greenspans failure to prevent the 2008 crisis, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) grew in prominence. While not exactly being the guiding principle of the Fed like Austrian Economics was to Greenspan, MMT provides a sort of justification for the current rapid expansion of the debt and loose monetary policy. In short it focuses on two claims:

Government Spending is Not Revenue-Constrained

Governments that issue their own currency cannot "run out" of money in the same way households or businesses can. They can always just issue more debt, or print more money. So long as a country’s debt is issued in their own currency, default should be impossible.

Inflation as the Main Constraint

The primary limitation on government spending is inflation, not solvency or debt levels. So long as inflation remains low, deficit spending, and loose economic policy is acceptable.

Unlike Keynesian or Monetarist economists, who see government debt and deficits as long-term risks that must be managed, MMT disregards traditional concerns about debt levels. MMT theorists argue that so long as inflation is under control, the size of the debt is irrelevant, a view that directly contradicts the fiscal caution espoused by more mainstream schools of thought. There’s also the perverse incentive this creates, whereby if governments have no reason to keep spending under control, with the tacit approval of economists, then there’s no limit to how many insanely expensive spending projects they can dream up. In reality this has proven to be true, as both the Republicans and Democrats have dropped discussion of the debt as a talking point, with Obama, Trump and Biden all drastically increasing the debt and deficit.

This theory isn’t just a post-hoc justification for high government spending though, as there is at least some grounds to believe that inflation is the key indicator of a debt’s sustainability. After all, so long as a government is funding debt through more debt, or issuing of new currency, the overall market for dollars should reflect the sustainability of that debt. If inflation is too high, it means that fiscal + monetary policy is too loose to sustain for the market, and if it’s acceptably low, then it means the current policy isn’t injecting too much liquidity into the market. Unfortunately this does little to contend with the exponentially growing nature of the debt, as eventually it becomes unsustainable.

No suggestion is really made for what to do when this happens, other than increase interest rates. As interest rates rise, governments that have relied on cheap borrowing face significant financial strain. The cost of servicing existing debt increases, leaving less room for discretionary spending on other priorities. This creates a vicious cycle: rising interest rates force governments to borrow more just to cover the cost of previous debt, potentially leading to inflation if governments turn to printing more money.

Interestingly, this is basically where we are finding ourselves now, and brings us back to the original impetus for this writeup. The debt indeed is at an all time high, and with increased interest rates to fight inflation, the cost of servicing that debt is rapidly increasing. As loans from the low interest days of the 2010s come due, they have to be replaced by the high interest rate loans of today, which is potentially unsustainable.

Conclusion:

At this point, my original intention of making a simple post in response to an internet disagreement has turned into a 20,000 word monster. I already have a big warning on top of my screen that this post is too long for email, and I realize most people won’t sit down and read an hour long essay in a single sitting anyways, so I’ll be breaking this up into three parts. Perhaps this has gotten out of hand, but it’s been a few years since I studied economics in a professional setting, so this deep dive is more of a confirmation of my own understanding, cross-referenced to other sources, than it is for you.

In my Part 2, I’ll explain the different tools the Fed has at its disposal and the four potential ways out of the current debt-crisis. In Part 3 I’ll give my opinion as to what the role of the Fed should be, why most people who hate or doubt the Fed are wrong, and offer some additional theories of my own.

If this is a topic that interests you, feel free to subscribe where I talk about Economics, Politics, Demographics all in pursuit of understanding the world you and I live in.

As always, I appreciate your comments and thoughts. Thank you for reading.

The goal of maintaining a stable level of prices over time, with low and predictable inflation rates. A focus on price stability helps prevent both inflation (rapid price increases) and deflation (falling prices), fostering economic certainty and trust in the currency.

Example: The Swiss National Bank (SNB) targets inflation near 2%, prioritizing long-term stability in prices.

A mandate to achieve the highest possible level of employment without triggering excessive inflation. Central banks with this objective aim to support economic conditions that lead to job creation and full employment.

Example: The Federal Reserve operates under a dual mandate: keeping inflation around 2% while maximizing employment.

The goal of maintaining the stability of the financial system by ensuring banks, financial institutions, and markets operate smoothly and efficiently. It includes preventing crises, managing systemic risks, and ensuring liquidity in times of stress.

Example: The Bank of England monitors financial markets and regulates financial institutions to prevent systemic risks that could lead to financial crises.

A mandate to promote sustained economic growth, industrial development, and improved living standards. This can include policies aimed at credit expansion, support for strategic sectors, and fostering infrastructure investment.

Example: The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) supports economic development by guiding credit to priority sectors, controlling interest rates, and managing liquidity, often focusing on both stability and growth.

A policy where the central bank aims to maintain a fixed or tightly controlled exchange rate between its currency and another currency or a basket of currencies. This reduces volatility in trade and financial flows but limits domestic monetary policy flexibility.

Example: The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) operates a currency board system, pegging the Hong Kong dollar to the US dollar.